This page answers a few of the questions I reckon folk are most likely to ask about the project. A lot of the answers here are explained in more detail within the Report, but given that’s quite lengthy I don’t expect everyone to have read it. Plus, it’s always handy to have a quick version to refer to.

128 Local Councils? That's a bit extreme, isn't it?

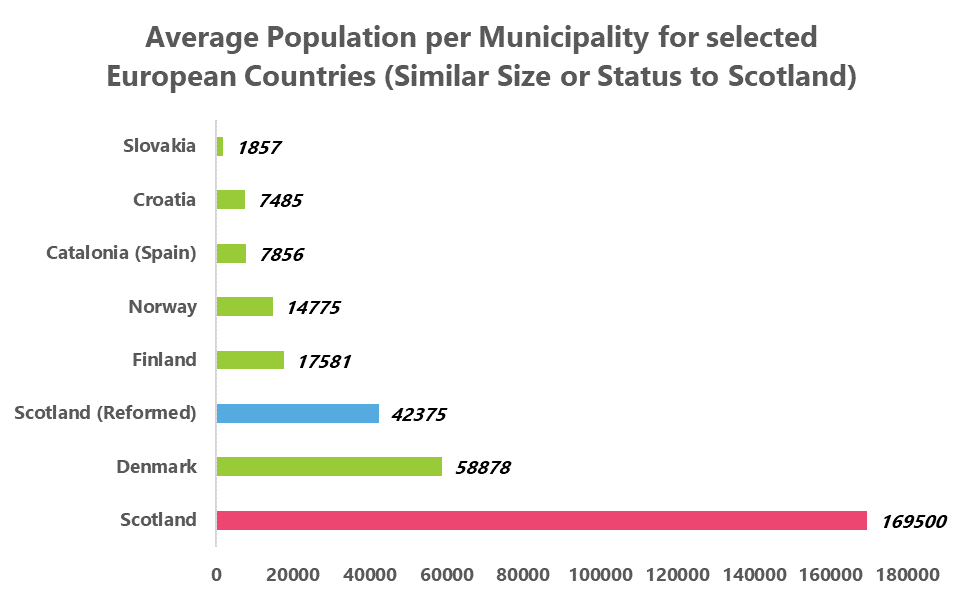

Only when your sole point of reference is the current situation in Scotland and the UK as a whole. For obvious reasons, people aren’t generally aware of how local government works in other countries, the clue being in the name. It isn’t therefore widely known that the UK, and our next door neighbour Ireland, have by far the largest “local” councils anywhere in Europe. With almost five and a half million folk spread across 32 of them, the average population of a Scottish council is nearly 170,000.

Outside of the UK and Ireland, the next largest councils are in Denmark, where they are approximately 59,000 people on average. That’s one-third the size of Scotland’s – and this in a country with a roughly similar population to ours, covering a land area about half the size. The table below shows the average population per council for some countries with a similar size or (in the case of Catalonia) status to Scotland.

Reforming Scottish local government to the model outlined in this project would reduce our average population per council to 42,375. That’d bring us below the Danish level, which makes sense given our larger land area, but still at the upper end of the scale. That seems like a perfectly reasonable balance to strike, and one far better than our current nonsensically huge councils.

It's a nice idea, but wouldn't it be expensive?

Being quite honest, yes. However, the premise that expense should mean we don’t do it is a very “cost of everything, value of nothing” argument. All democracy costs money – to run the elections, to employ people to carry out the administrative functions of government, and to pay the elected representatives and their staff. In general we consider that a worthwhile investment because we believe democracy is important. Local democracy is no less important than national democracy, and in fact may even be more important given it’s closer to people’s everyday lives.

However, there are a few things to bear in mind about cost. The first is that although this project proposes 4.3 times as many units of local government as at present, it only suggests 2.5 times as many elected representatives for them. That’s still more money for councillors, but not as much as might initially be assumed.

It’s also very common to talk about delivering services over wider areas as being more “efficient”. That’s often true, and there’s nothing about this project that precludes municipalities working together to deliver such efficiencies. For example, Caithness and Sutherland might well opt to run a joint refuse collection and disposal service, or the four Borders municipalities might create a shared bus service.

The expectation that larger equals more efficient doesn’t necessarily always ring true though. There’s a greater possibility of human error creeping in when councillors are over-stretched and don’t know the ins and outs of every local area they might take e.g. planning decisions about, which can be costly if a badly thought through proposal passes.

Finally, the up-front annual cost of running more local government is easier to imagine than the prospective economic benefits from doing so. Councils taking better decisions that are more suited to the people they represent, improving the state of the local society, environment and economy could more than make up for their costs.

This is very complex. How long would it take to do?

You’d need a more expert head than me to answer that question, but I’d expect this to be a lengthy process. Somewhere between five and ten years seems reasonable, depending on how it’s approached. Right at the start, would initiating a process of reform and setting the basic framework for it require legislation, simple parliamentary approval, or just ministerial action? Legislation could take months by itself, whereas a ministerial decision could start the process within weeks of taking office.

Then we’d need to get the balance right between the input from expert commissions (which may include ordinary residents as part of that expertise) tasked with actually drawing up boundaries and broader democratic engagement with residents beyond traditional consultations, both of which are time consuming. Public engagement is key to ensuring we end up with a much better and longer-lasting settlement than we currently have.

After that we definitely would need legislation to actually implement the resulting output, and then there needs to be a period of time before that legislation formally enters into force. We’d need to identify transition arrangements, locate headquarters and offices or build new ones if necessary, work out how and where to send existing council staff, and how many more need to be recruited.

It’s also not necessarily the case this would have to happen in one fell swoop. It could be staggered over the period, coming into effect region-by-region over the course of a few years. Starting in places like Tayside or Dumfries and Galloway, which consist wholly of existing councils, before moving on to thornier areas like Clyde and the Highlands might make sense.

Would we really need Regional Councils? Doesn't the Scottish Parliament basically do that job?

The Scottish Parliament is a legislative body, which means its primary purposes should be to scrutinise and pass legislation, hold the government to account, and generally provide the overall direction of political travel for Scotland as a whole. That last point also applies to the Scottish Government, which has more ability than Parliament to handle operational aspects of regional governance, but still has limited capacity. It therefore makes sense to have a layer of government that handles wider regional issues that isn’t tied to the national parliament.

Two-tier local government is still quite common in countries with Federal or Devolved systems, though examples such as Austria’s Districts and Catalonia’s Comarques aren’t directly elected and are instead made up of municipal representatives. On the other hand, although they deal primarily with finance, the Basque Country’s three Foral Councils which exist due to the special status of the Basque Provinces are directly elected and have substantial influence. The geographic size of Scotland relative to our population also lends itself to a regional structure.

Is there any difference between City, Burgh, District and Island Councils?

For the most part, no. They are just descriptions. Unitary Authorities using the City and Island Council descriptors do differ from the other municipalities, but that’s a function of Unitary status not name. Although they don’t offer any difference in powers, there is a certain logic to how they’ve been applied to the proposed municipalities.

“City” means an urban area granted that title. “Burgh” is a large urban area that either covers a single town, a single town that is dominant over its environs, or a tightly bound pair of towns. “Island” means the Council consists entirely of islands. “District” is then a catch-all for every other area, which can be highly rural or well urbanised but without a large town.

Actual legislation about names should offer a degree of flexibility. “City” and “Burgh” should be bestowed by statute, but it shouldn’t be necessary for other areas to always formally go by “District”. A District that covers a historic Shire for example might simply go by e.g. “Berwickshire Council.”

Doesn't a 3% threshold for elections risk overly fractured politics?

That depends on your own personal and subjective view of what counts as fractured. Personally, I don’t think so. A 3% threshold has previously been recommended by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe for “well-established democracies”. Although that relates primarily to parliamentary elections, given the relatively lower stakes of local elections, I’d say the same logic applies. Scotland clearly is a “well-established” democracy so it isn’t like we need time for our politics to settle into a democratic rhythm or anything.

Beyond that, winning 3% allows parties to win seats, but does not guarantee they will do so. Most municipalities proposed in this project are too small for that to be enough when using the D’Hondt method. It depends partly on the performance of other parties and candidates, but Perth for example has the Greens come out at 3.1% of the vote without winning any of the 23 seats on the council. There’d have needed to be 28 seats before that level of support secured a Green seat.

Even if we assume a highly fractured vote share and say the break point is about 25 seats on the council for 3% to have a chance at delivering a seat, only 20 (16%) of the proposed municipalities have that many or more seats. On the other hand, 9 of the 10 regional councils do have at least that many. Also, if we were to use Sainte-Laguë instead of D’Hondt, the break point possibly comes as low as 15 seats, in which case just under two-thirds of municipalities would have enough seats.

Won't giving smaller municipalities more seats on regional councils unfairly give voters there more power than ones in larger municipalities?

In general terms, no, not at elections. At least not under the electoral system proposed as part of this project. Remember that the last seat in each municipality is elected on the basis of the overall regional vote to deliver maximum proportionality. That means in most cases, every vote counts the same in terms of how much it will determine the overall spread of seats on the council. Obviously, the commissioners then elected from a smaller municipality do have more voting weight on the Council, but that’s the point.

Only in cases where one party is overwhelmingly dominant in most or all municipalities in a region is this a possible issue. It would then be possible to win slightly too many of the directly elected commissioners from small municipalities, and knock proportionality of the overall region off slightly. Based on 2017 results this wouldn’t happen anywhere with even the most lop-sided region, Dumfries and Galloway, delivering ideal proportionality within the bounds of D’Hondt.

What are the 1973 and 1994 Acts?

Mentioned regularly on the Region pages, these are the Acts of the UK Parliament that implemented the previous (1973) and current (1994) systems of local government. Both of these were enacted by Conservative governments, though the groundwork for the 1973 Act was the results of the Wheatley Commission, set up by a Labour government.

By the way, who are you?

I’m Allan Faulds, a professional nerd. I have a particular (amateur) interest in democratic structures and systems, which is how this project came about. I also run the Scottish polling and elections project, Ballot Box Scotland. You possibly guessed that based on the fact this site is a subdomain of that one.